Behind the Scenes- Glass Ceiling Records

Relational Anthropology: Naming What Has Always Been There

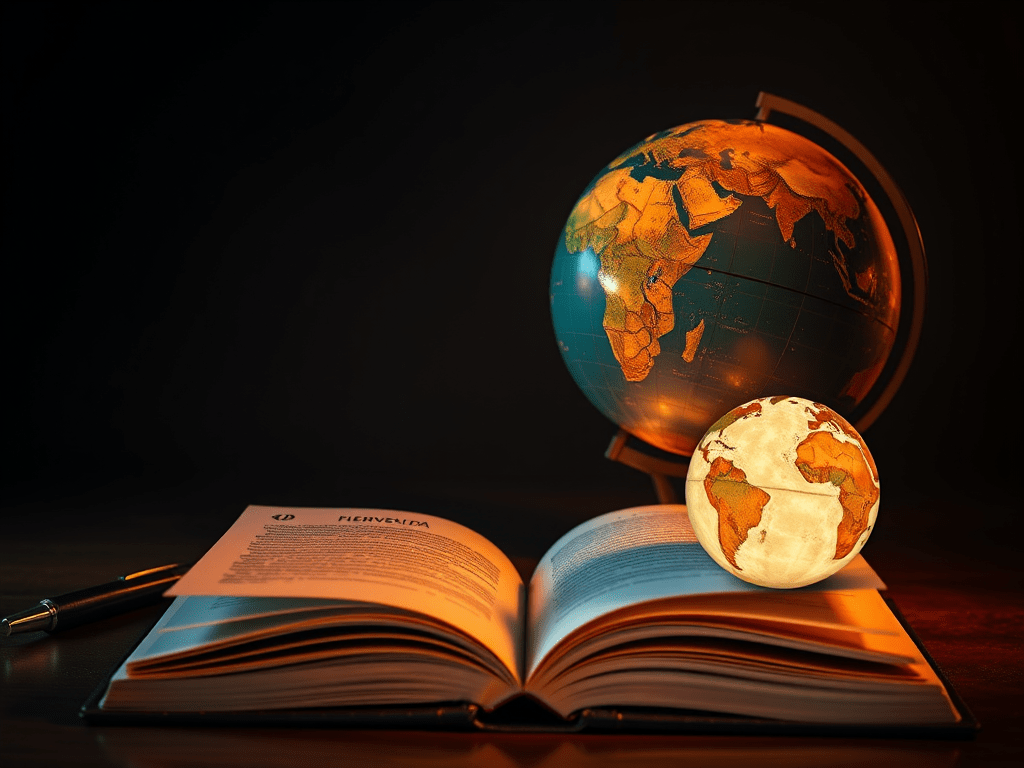

Every so often, a concept arrives that feels less like invention and more like recognition. That’s what happened when I started asking whether “Relational Anthropology” was a real thing. The deeper I looked, the clearer it became: anthropology has been practicing relational thinking for decades — it just never named the lineage cleanly. The field has always been built on relationships between people, land, language, ritual, power, and meaning. We’ve simply scattered that truth across subfields instead of claiming it as a unified framework.

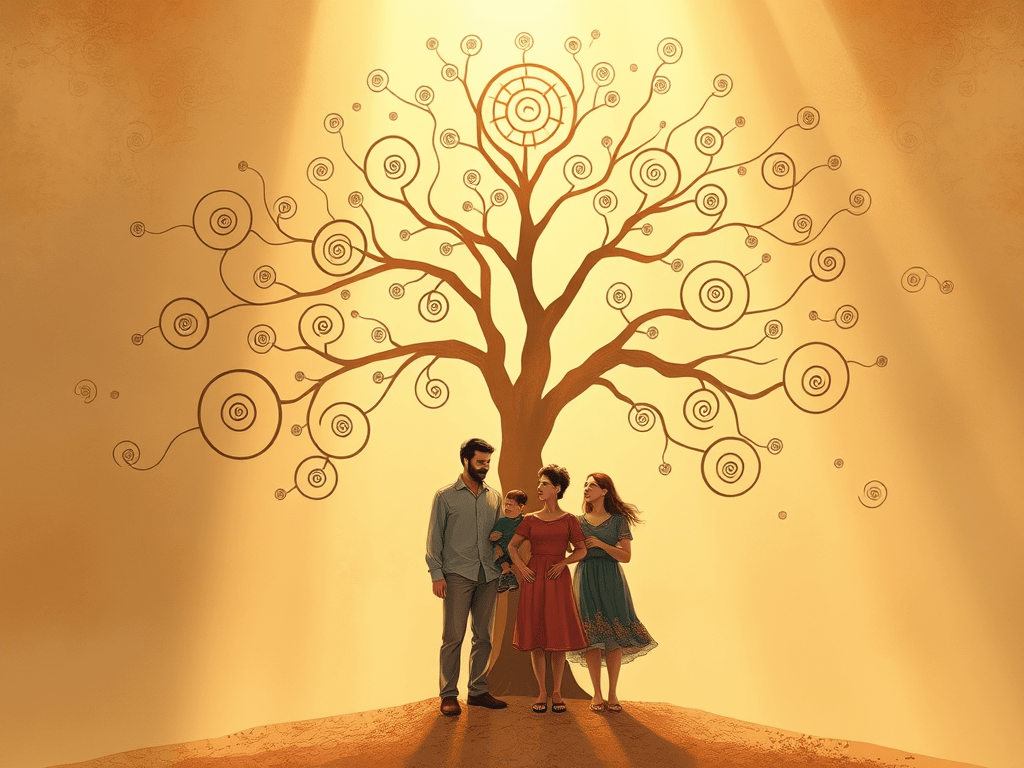

Look closely and the pattern is unmistakable. Cultural anthropology explores meaning through intersubjectivity and lived experience. Linguistic anthropology traces relationships between language, identity, and worldview. Biological anthropology examines humans as relational beings shaped by ecology and evolution. Archaeology reconstructs past worlds through the relationships between objects, landscapes, and human behavior. Even ethnomusicology — often tucked into cultural anthro — treats sound as a relational event that creates social worlds. Every branch of the discipline is relational at its core, even if the textbooks don’t use the word.

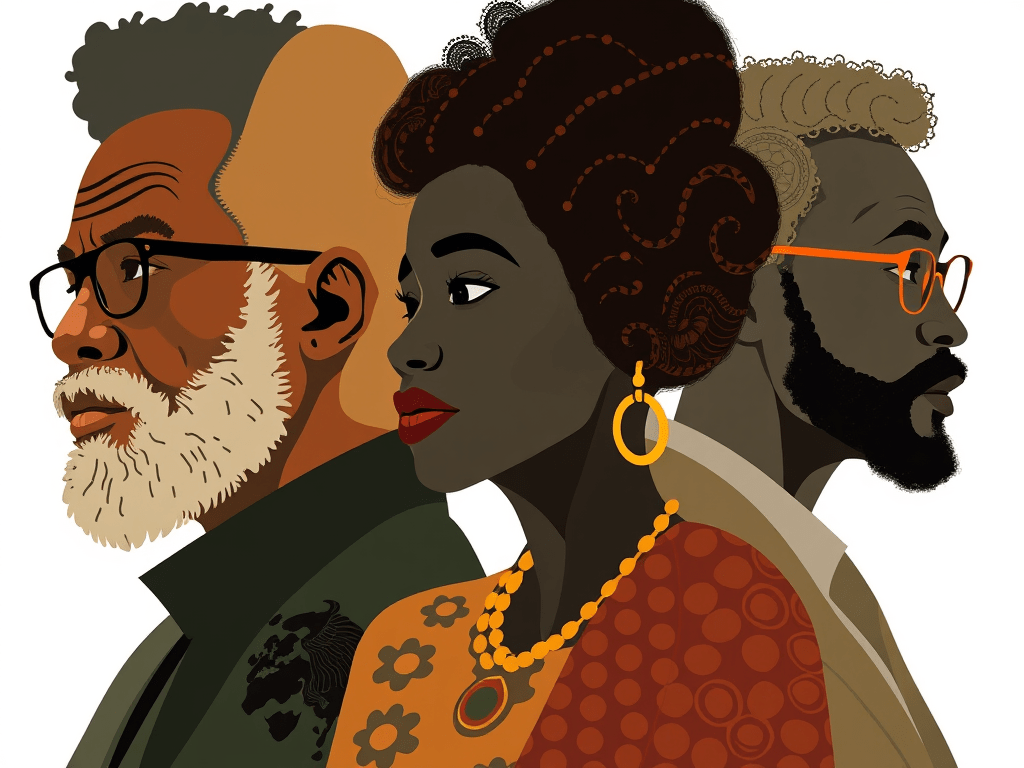

So why hasn’t the field named it? Because academia often fragments what is whole. It prefers categories, subfields, and methodological silos. But lived anthropology — the kind practiced by communities, artists, survivors, ritualists, and fieldworkers — has always been relational. It understands that knowledge is co‑created, not extracted. That meaning emerges between people, not inside isolated individuals. That culture is not a static object but a web of relationships constantly being made and remade.

By naming Relational Anthropology, we’re not inventing a new subfield. We’re acknowledging the connective tissue that has always held the discipline together. We’re giving language to the way many of us already work: through reciprocity, presence, emotional literacy, and co‑creation. We’re recognizing that anthropology is strongest when it honors relationships — between researcher and community, between past and present, between story and witness, between land and lineage.

Relational Anthropology is a reminder and a declaration: anthropology is not about studying people from a distance. It’s about entering into relationship with the worlds we seek to understand. And once we name that truth, we can finally teach it, practice it, and build with it intentionally — not as a hidden method, but as a living framework.

What do you think?