Lynching – A History

Did you know that lynching wasn’t made a federal hate crime until 2022, enacted between the Trump regimes? You might be surprised by quite a lot in the history of United States lynchings. It occurred to me that we weren’t taught much about it in school.

I was curious, so I asked Copilot.

Can you give me a comprehensive history of lynching in the United States?

Absolutely — here’s a detailed, historically grounded overview of lynching in the United States, tracing its origins, evolution, and legacy.

📜 Origins and Early Development (Pre–Civil War to Reconstruction)

- Definition: Lynching refers to extrajudicial killings carried out by mobs, often under the pretext of justice, without due process.

- Etymology: The term is often linked to Charles Lynch, a Virginia justice of the peace during the American Revolution, who led irregular courts to punish Loyalists.

- Early Use: Before the Civil War, lynching occurred in both the South and the West, often targeting alleged criminals, Indigenous people, and Mexican Americans.

- Post–Civil War Shift: After the abolition of slavery in 1865, lynching became a tool of racial terror aimed primarily at African Americans, enforcing white supremacy and the racial caste system.

📈 Peak Era of Racial Terror (1880s–1930s)

- Scale: Between 1882 and 1968, at least 4,743 lynchings were recorded; about 72% of victims were Black. Historians believe the true number is higher due to underreporting.

- Geography: Most occurred in the South (Mississippi, Georgia, Texas leading in numbers), but lynchings also took place in the Midwest, West, and border states.

- Victims Beyond Black Americans: Mexican Americans, Native Americans, Chinese immigrants, and Italian immigrants (notably the 1891 New Orleans mass lynching of 11 Italians) were also targeted.

- Accusations as Pretext: Common charges included murder, rape, or violating racial etiquette. Many accusations were fabricated or exaggerated to justify mob violence.

- Spectacle Lynchings: These were public events, sometimes attended by thousands, involving torture, mutilation, and burning. Photographs were sold as postcards.

⚖️ Resistance and Anti-Lynching Campaigns

- Black Press & Activists: Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s investigative journalism in the 1890s exposed lynching as a tool of racial control, not justice.

- NAACP Campaigns: The NAACP flew a flag outside its New York headquarters reading “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” and lobbied for federal anti-lynching laws.

- Legislative Failures: Despite repeated attempts, Congress failed to pass anti-lynching legislation for decades due to Southern opposition.

- Decline After 1930s: Public opinion began to shift, and lynching declined after 1935, though racially motivated killings continued in other forms.

🕊 Civil Rights Era and Modern Recognition

- 1950s–1960s: Lynchings became less frequent but persisted; the 1955 murder of Emmett Till galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

- Great Migration Impact: As African Americans moved north and west, lynching followed them, though often in less public forms.

- Contemporary Reckoning:

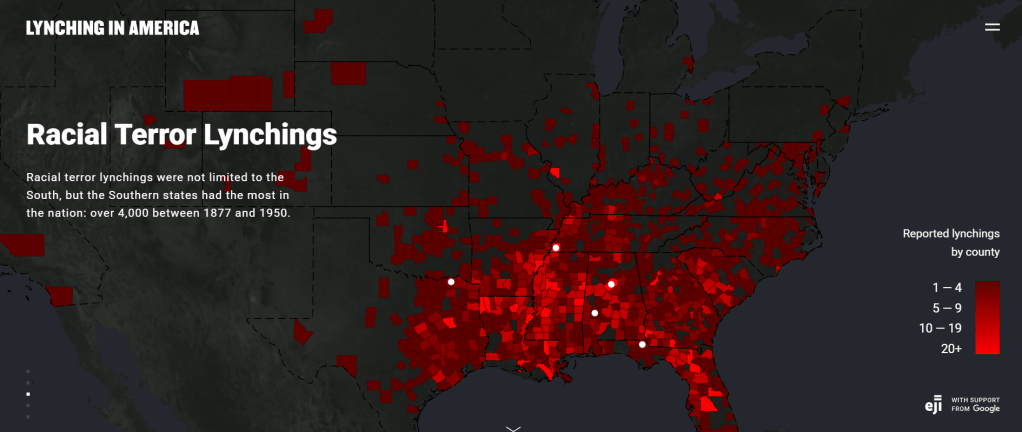

- Equal Justice Initiative’s Lynching in America report documented over 4,000 racial terror lynchings between 1877–1950.

- In 2022, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act finally made lynching a federal hate crime.

- Memorials, such as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, now honor victims.

📊 Key Statistics (1882–1968)

| Group | Recorded Victims | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Black Americans | 3,446 | ~72% |

| White Americans | 1,297 | ~27% |

| Mexican/Mexican American | 71 | — |

| Native American | 38 | — |

| Chinese | 10 | — |

| Japanese | 1 | — |

🔍 Historical Significance

Lynching was not random violence — it was a systemic tool of racial, political, and economic control. It reinforced segregation, suppressed Black political participation, and maintained white dominance through terror. Its legacy continues to shape racial dynamics, policing, and justice in the U.S.

If you’d like, I can map lynching patterns alongside Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, and migration data to show how racial terror was embedded in broader systems of control — which could be powerful for your advocacy and educational toolkits. Would you like me to prepare that next?

Can you tell me more about the white victims of lynching?

Yes — while lynching in the United States is most often (and rightly) remembered as a tool of racial terror against Black Americans, white victims made up a significant minority of recorded cases, and their stories reveal a broader picture of mob violence, frontier justice, and political conflict.

📊 Scope and Numbers

- Between 1882 and 1968, records show about 1,297 white victims of lynching — roughly 27% of the total.

- These victims were concentrated in certain regions and time periods:

- Early frontier and Western territories (mid–late 19th century) saw higher proportions of white victims, often tied to disputes in mining camps, cattle towns, and areas without established courts.

- In the South, white victims were far fewer proportionally, but still present — often in cases involving accusations of murder, sexual assault, or political betrayal.

🗺 Patterns and Contexts

1. Frontier “Justice” and Lawlessness

- In the West, lynching was sometimes framed as a form of “community justice” in areas with weak legal systems.

- White victims here were often accused of cattle rustling, stagecoach robbery, or murder.

- These lynchings were less about racial hierarchy and more about perceived threats to property, order, or local power.

2. Political and Labor Conflicts

- Some white victims were targeted for their political affiliations — e.g., being suspected Unionists in Confederate states during and after the Civil War, or being accused of siding with labor unions during strikes.

- In mining towns, white immigrants (especially Italians, Finns, Germans) could be lynched during ethnic or labor disputes.

3. Interracial Solidarity or “Betrayal”

- In the Jim Crow South, a small number of white people were lynched for aiding Black neighbors, opposing segregation, or being accused of interracial relationships.

- These cases reinforced the racial order by punishing perceived “race traitors.”

4. Ethnic and Immigrant Targets

- Some white victims were part of ethnic groups considered “outsiders” at the time:

- Italian Americans — most infamously in the 1891 New Orleans lynching of 11 Italian immigrants.

- Eastern and Southern Europeans — sometimes targeted in rural or industrial towns.

- Jewish Americans — e.g., Leo Frank in Georgia, 1915, lynched after a highly publicized and biased trial.

⚖️ Differences in Public Perception

- White victims were less likely to be lynched as public spectacles compared to Black victims, though exceptions existed.

- Press coverage often framed white lynching victims as criminals or outlaws, whereas Black victims were frequently portrayed through racist tropes to justify racial terror.

- The systemic function differed: lynching of Black people was a tool of racial control, while lynching of white people was more often tied to local disputes, lawlessness, or political suppression.

🧩 Why This Matters for the Larger History

Understanding white victims of lynching:

- Highlights that mob violence was a flexible tool — used to enforce racial hierarchy, but also to police class, political, and ethnic boundaries.

- Shows how frontier violence and racial terror were connected in the American imagination of “justice.”

- Underscores that while white victims existed, the scale, purpose, and brutality of lynching against Black Americans was distinct and systemic.

If you’d like, I can map the white victim cases by region, decade, and cause — which would make visible the shift from frontier vigilantism to racially targeted terror, and could be a powerful comparative layer for your systemic violence frameworks. Would you like me to prepare that next?

Please map lynching patterns alongside Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, and migration data to show how racial terror was embedded in broader systems of control.

Lynching, Jim Crow, voter suppression, and Black migration weren’t parallel stories — they were interlocking systems that moved in tandem. Here’s a clear look at how they reinforced one another across time and region, and how you can visualize the patterns for advocacy and education.

Patterns over time and space

1877–1910: Reconstruction’s reversal and the foundations of racial control

- Lynching: Southern lynchings proliferate as Reconstruction ends; vigilante regimes solidify where slavery-intensive economies had structured racial caste, while Western lynchings reflect frontier “law” dynamics with multi-ethnic victims.

- Jim Crow/Black Codes: Postwar Black Codes evolve into formal Jim Crow architecture, codifying segregation and subordinating labor and mobility.

- Voter suppression: Early disfranchisement escalates: poll taxes, literacy tests, and administrative barriers begin collapsing Black voter rolls, setting the template for mass political exclusion.

1910–1930: Peak terror and the First Great Migration

- Lynching: High-frequency, often “spectacle” lynchings in the South enforce the racial order; national datasets show persistence beyond the Deep South, aligning with former slave economies and “Little Dixie” corridors.

- Migration link: The First Great Migration accelerates as people flee terror and seek industrial jobs; county lynching hot spots correlate with outflows to Midwest/Northeast cities.

- Jim Crow expansion: States deepen segregation across schools, transit, housing, and marriage, entrenching second-class citizenship in law.

- Disfranchisement entrenched: Poll taxes and literacy tests routinize exclusion; registration collapses (e.g., Mississippi/Louisiana) document the scale of disenfranchisement and its durability.

1930–1950: Decline in lynching counts, continuity of coercion

- Lynching: Public lynchings gradually decline after mid-1930s amid national scrutiny, but targeted killings and mob violence persist; geography still mirrors slavery-era economies.

- Migration link: Continued South-to-North/West movement; Red Summer 1919’s urban pogroms foreshadow conflicts in receiving cities, even as migrants gain new footholds.

- Jim Crow stability: Segregation remains comprehensive; enforcement through police, courts, and extrajudicial intimidation sustains the caste system even as overt lynchings ebb.

- Voting: Disfranchisement holds firm until mid-1960s; barriers remain the spine of Southern political monopoly.

1950–1970: Civil rights breakthroughs and the Second Great Migration

- Lynching to law-and-order repression: Fewer public lynchings, but racially motivated killings still occur; formal Jim Crow begins to crack under Brown (1954) and federal civil rights statutes.

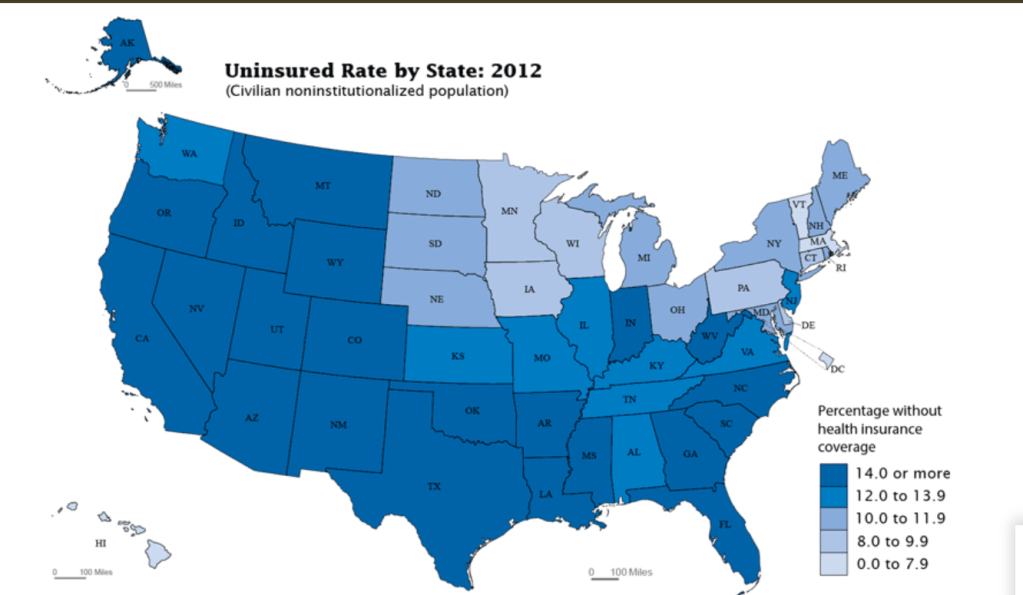

- Migration link: War/postwar jobs drive the Second Great Migration to Northern/Western metros; structural barriers (redlining, covenants) constrain opportunity and reproduce segregation outside the South.

- Voting rights: 1964–1965 civil rights laws expand access, but the legacy of disfranchisement shapes representation for decades.

Mechanisms of control across systems

- Terror as enforcement for law: Lynching worked with Jim Crow statutes to punish perceived breaches of racial hierarchy, producing a regime where extrajudicial violence reinforced legal segregation and economic subordination.

- Political monopoly through fear and rules: Mob violence, coupled with poll taxes, literacy tests, and administrative discretion, stripped political power and shielded segregationist policy from electoral challenge.

- Forced migration as survival strategy: EJI’s mapping and federal demography show that terror and legal repression were primary push factors; receiving cities offered wages and relative safety but adopted new instruments of segregation (e.g., redlining), diffusing the caste system into new geographies.

Regional comparison snapshot

| Region | Lynching prevalence | Jim Crow regime | Primary suppression tools | Migration dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep/Lower South | Highest, including “spectacle” lynchings; clusters track slavery economies | Maximal de jure segregation across life domains | Poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, police/court intimidation | Major outflows to Midwest/Northeast, later West |

| Border Upper South | High but more heterogeneous | Strong segregation; some urban variation | Similar toolset with county-level discretion | Outflows to mid-Atlantic/industrial hubs |

| Midwest/West | Lower for Black victims, but present; Western multi-ethnic mob violence | Formal Jim Crow weaker, but segregation via policy/practice (e.g., covenants) | Administrative barriers, violence during unrest, residential exclusion | Major destinations; redlining constrains opportunity |

What this mapping makes visible

- Spatial continuity: The tight alignment between slavery’s economic geographies, lynching clusters, and the strongest Jim Crow regimes demonstrates that terror was the extralegal arm of a legal caste order.

- Temporal sequencing: As disfranchisement hardened in the 1890s–1910s, lynching peaked; as public lynchings waned, statutory and bureaucratic controls persisted until mid-century civil rights interventions.

- Migration as testimony: The Great Migration traces lived decisions to exit terror zones; overlaying flows with lynching densities and disfranchisement regimes converts “push factors” into measurable structure.

Maps and Meaning

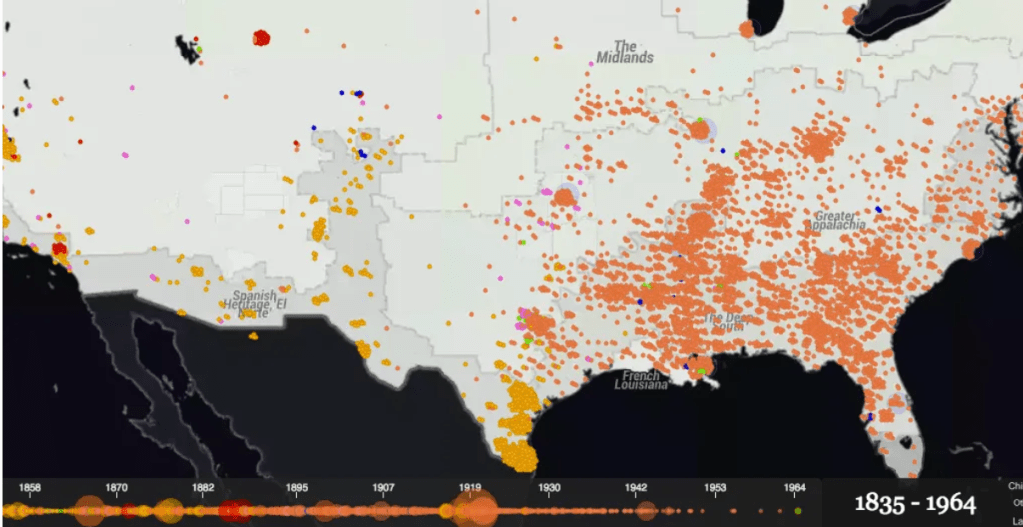

I could construct the maps myself, but I think it’s far better to let the statisticians handle the data, and the already have. There are several sites that have interactive maps, tables, and other resources to investigate the data further.

The Great Migration

The Census Bureau

Here I’ve taken some screenshots to share.

As I looked through visual representations for this post, I was struck by the similarity of these maps to other important maps.

Key datasets and historical anchors

- Jim Crow legal regime (state/local): State-by-state segregation statutes, miscegenation bans, school and public accommodations segregation; broad synthesis of purpose, reach, and timeline (Black Codes → Plessy → Civil Rights Act).

- Voter suppression (mechanisms and timelines): Disfranchisement via poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses; steep registration collapses (e.g., Mississippi and Louisiana); modern inflection points post–Shelby County v. Holder (2013).

- Great Migration flows (push/pull, destinations): Approximately 6 million Black Southerners relocated to Northern, Midwestern, and Western cities (1910–1970), with distinct First (1910–1940) and Second (1940–1970) waves and clear destination patterns (Chicago, Detroit, NYC, Philadelphia; later West Coast). University of Washington mapping shows decade-by-decade origins/destinations and the migration’s political/economic consequences.

- Racial terror lynching (geography/time): Over 4,000 documented racial terror lynchings in the South (1877–1950), with interactive county mapping and Great Migration overlays showing direct spatial links between lynching clusters and out-migration corridors. Research teams using NAACP/Chicago Tribune datasets confirm national scope (1883–1941), with clusters tied to slavery-intensive economies and weak law enforcement in the West. Smithsonian’s overview contextualizes multi-ethnic targets and periodization (1830s–1960s).

References

ABC News. (2020, July 23). Timeline: Voter suppression in the U.S. from the Civil War to today. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/timeline-voter-suppression-us-civil-war-today/story?id=72248473

Britannica. (n.d.). Jim Crow law. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law

Britannica. (2025, August 14). Lynching in the United States. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/lynching

Census Bureau. (n.d.). Data visualizations. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/020/

Equal Justice Initiative. (n.d.). Lynching in America. Equal Justice Initiative. https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore

History.com Editors. (2023, August 21). Jim Crow laws. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/articles/jim-crow-laws

Learning for Justice. (2023, June 13). Voter suppression timeline. Learning for Justice. https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/Voter-suppression-timeline–06132023_0.pdf

NAACP. (n.d.). History of lynching in America. NAACP. https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america

National Archives. (n.d.). The Great Migration. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration

Penn State University. (2019, May 15). Map reveals that lynching extended far beyond the deep South. Penn State University. https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/map-reveals-lynching-extended-far-beyond-deep-south-0

Smithsonian Magazine. (2017, April 28). Map shows over a century of documented lynchings in the United States. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/map-shows-over-a-century-of-documented-lynchings-in-united-states-180961877/

University of Washington. (n.d.). Black migration. University of Washington. https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/black_migration.shtml

University of Washington. (n.d.). Map: Black migration. University of Washington. https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/map_black_migration.shtml

Wikipedia. (n.d.). List of Jim Crow law examples by state. In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Jim_Crow_law_examples_by_state

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Lynching in the United States. In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_in_the_United_States

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Voter suppression in the United States. In Wikipedia. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voter_suppression_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_in_the_United_States

https://www.britannica.com/topic/lynching

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america

https://lynchihttps://abcnews.go.com/Politics/timeline-voter-suppression-us-civil-war-today/story?id=72248473nginamerica.eji.org/explore

https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/map-reveals-lynching-extended-far-beyond-deep-south-0

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/map-shows-over-a-century-of-documented-lynchings-in-united-states-180961877/

https://www.history.com/articles/jim-crow-laws

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Jim_Crow_law_examples_by_state

https://www.britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voter_suppression_in_the_United_States

https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/020/

https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/Voter-suppression-timeline–06132023_0.pdf

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/timeline-voter-suppression-us-civil-war-today/story?id=72248473

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/timeline-voter-suppression-us-civil-war-today/story?id=72248473

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration

https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/black_migration.shtml

https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/map_black_migration.shtml

What do you think?