Loveland’s FOR-PROFIT Jail

Copilot, I recently learned that our local jail is a “for-profit” jail. What does that mean?

A “for-profit” jail is a correctional facility operated by a private company that earns revenue by incarcerating people under government contracts.

Here’s a breakdown of what that means and why it matters:

🏢 What Is a For-Profit Jail?

- Privately operated: Unlike public jails run by local or state governments, for-profit jails are managed by corporations under contract with government agencies.

- Revenue model: These companies are paid a fixed amount per inmate per day or per available bed, regardless of whether it’s occupied.

- Government contracts: Local, state, or federal governments outsource incarceration to these companies, often citing cost savings or capacity issues.

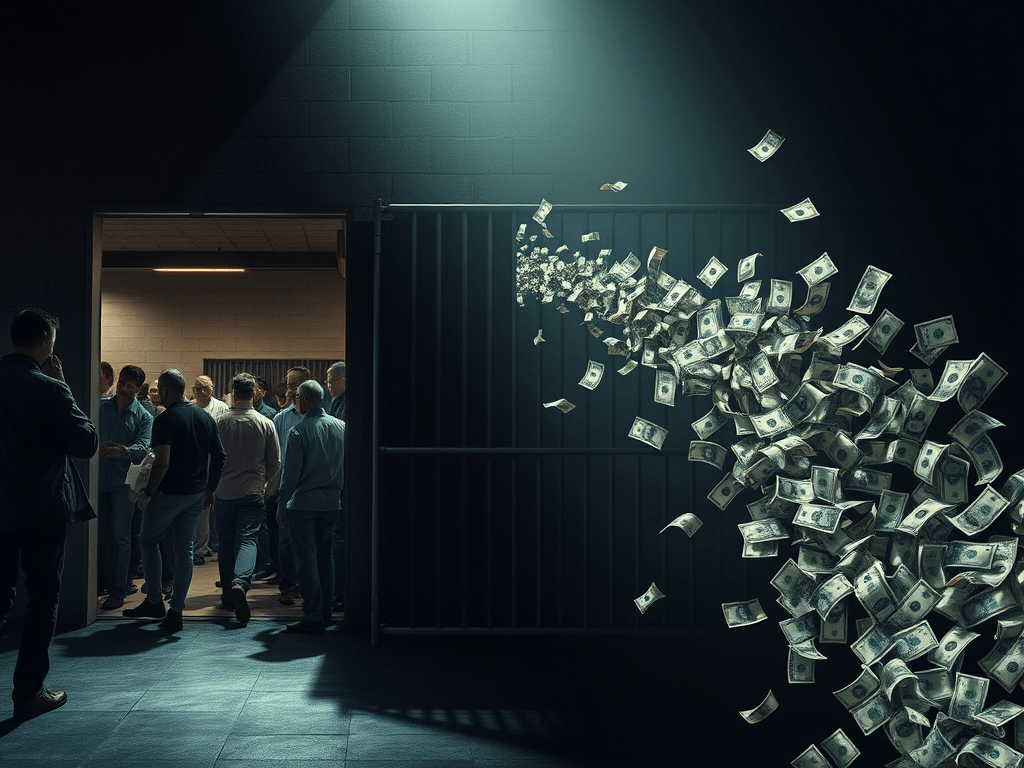

💰 How Profit Is Made

- Cost-cutting incentives: To maximize profits, companies may reduce staffing, healthcare, food quality, or rehabilitation programs.

- Occupancy guarantees: Some contracts include “lockup quotas” or “bed guarantees,” requiring governments to keep jails at a certain occupancy level or pay penalties.

- Construction and operation: Some companies not only run the jails but also build them, creating long-term financial arrangements with local governments.

⚖️ Controversies and Criticisms

- Ethical concerns: Critics argue that profit motives conflict with justice and rehabilitation, incentivizing longer sentences or harsher policies.

- Accountability: Private jails may lack transparency and oversight compared to public institutions.

- Safety and outcomes: Studies have shown that private facilities often underperform in terms of inmate safety, staff training, and rehabilitation services.

📍 Local Relevance in Colorado

If your local jail in Loveland is for-profit, it likely operates under a contract with Larimer County or the state of Colorado. You can check the jail’s management details on the Larimer County Jail website or request contract information through public records.

What happens if crime is actually reduced in a place with a for-profit jail? (After all, isn’t that the purpose of pumping all of that funding into “public safety?”)

If crime drops in a region with a for-profit jail, the facility may face financial strain due to fewer incarcerations—despite public safety improving. This creates a tension between profit motives and justice outcomes.

Here’s how that dynamic plays out:

📉 Reduced Crime = Fewer Inmates = Lower Revenue

- For-profit jails earn money per inmate per day, so a drop in crime means fewer people incarcerated and less income.

- Some contracts include occupancy guarantees or “lockup quotas,” requiring governments to pay for a minimum number of beds—even if they’re empty.

- This can lead to perverse incentives: pressure to maintain incarceration rates through harsher policing, longer sentences, or detaining people for minor infractions.

💸 Public Safety vs. Profit Motives

- Public safety funding is meant to reduce harm, improve community well-being, and prevent crime.

- But in a for-profit model, success (less crime) undermines the business model, creating a structural conflict.

- This can distort policy decisions—favoring punitive approaches over prevention, treatment, or rehabilitation.

⚠️ Real-World Consequences

- Policy resistance: Efforts to decriminalize, divert, or reduce jail populations may be opposed by stakeholders with financial interests in incarceration.

- Budget misalignment: Instead of reinvesting savings from reduced crime into community programs, funds may be locked into long-term jail contracts.

- Community harm: The system may prioritize revenue over outcomes, leading to over-policing, racial disparities, and reduced trust in institutions.

🛠️ Advocacy Leverage Points

- Audit contracts: Look for occupancy guarantees, cost-per-bed clauses, and renewal terms.

- Push for reinvestment: Advocate for redirecting public safety funds into housing, mental health, and violence prevention.

- Expose contradictions: Use public testimony and data to highlight how reduced crime should lead to reduced incarceration—not financial penalties.

In this for-profit incarceration system, who pays?

In a for-profit incarceration system, taxpayers foot the bill—while private companies collect revenue. Families of incarcerated individuals also bear hidden costs, and local governments may face financial penalties if jail beds go unused.

Here’s how the payment structure breaks down:

🏛️ Who Pays Directly?

- Local, state, and federal governments contract with private jail operators and pay them per inmate per day. These funds come from public budgets, meaning taxpayers ultimately fund the system.

- Neighboring jurisdictions and federal agencies (like ICE or the U.S. Marshals Service) may rent jail beds from counties, creating additional revenue streams for local governments—but still funded by public dollars.

💸 Hidden Costs for Families and Communities

- Families of incarcerated people often pay for phone calls, commissary items, transportation, and legal support. These costs can be devastating—especially for low-income households.

- Communities lose economic stability when breadwinners are jailed, and children face long-term emotional and financial harm.

⚠️ Occupancy Guarantees and Financial Risk

- Many contracts include “lockup quotas” or minimum occupancy clauses, requiring governments to pay for a certain number of beds—even if crime drops and fewer people are jailed.

- This means local governments may be penalized for reducing incarceration, creating a perverse incentive to maintain or increase jail populations.

📊 National Spending Snapshot

- $80.7 billion is spent annually on public prisons and jails.

- $3.9 billion goes to private facilities.

- Over 4,000 companies profit from incarceration—from jail operators to telecom and food vendors.

🔍 Colorado Context

In Colorado, counties like Larimer may contract with private operators or lease beds to federal agencies. These arrangements can be found through public records or budget audits. If you’re tracking local jail contracts in Loveland, I can help you draft a records request or analyze budget line items.

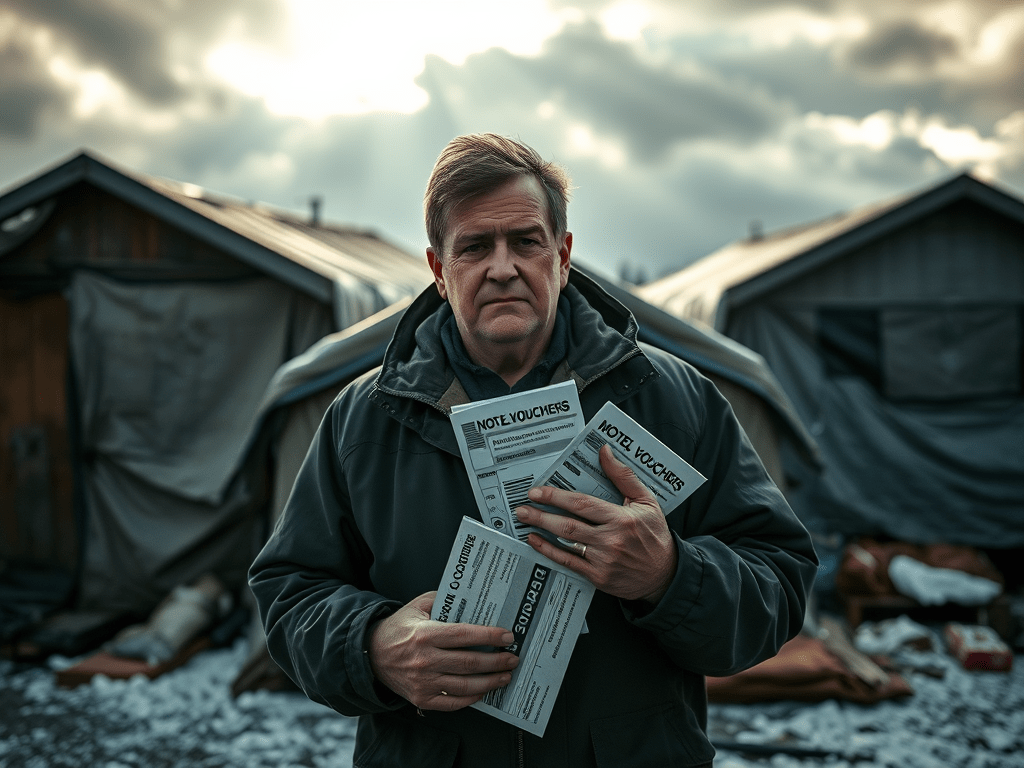

But we’re receiving reports from the homeless that they are being charged directly, upwards of $3000, per jail stay.

Yes, in Colorado and elsewhere, homeless individuals can be charged thousands of dollars for jail stays—often through court-imposed fines, fees, and “pay-to-stay” policies. These charges can accumulate even when the person is jailed for minor infractions or simply cannot afford bail.

Here’s how this system works and why it’s especially harmful:

💸 How Homeless People End Up Owing Thousands

- Booking and daily jail fees: Some jurisdictions charge inmates for each day they’re incarcerated—known as “pay-to-stay” fees. These can range from $30 to over $100 per day, quickly adding up to thousands.

- Court fines and surcharges: Even for minor offenses like trespassing or panhandling, courts may impose fines, administrative fees, and surcharges.

- Failure-to-pay penalties: If someone can’t pay, they may face additional fees, license suspension, or even re-incarceration.

- Restitution and legal costs: Courts may also charge for public defenders, probation supervision, or restitution to alleged victims.

⚠️ Colorado-Specific Examples

- In Denver, jail costs taxpayers $164 per night, and many beds are occupied by homeless individuals. Public defenders actively work to keep them out of jail to reduce costs and harm.

- In Colorado Springs, dozens of homeless people were jailed for unpaid fines related to panhandling or jaywalking. The city later agreed to pay them $125 per day they were wrongfully incarcerated.

- A report from the University of Denver’s Homeless Advocacy Policy Project found that criminalizing homelessness leads to a cycle of incarceration and debt, with fees often exceeding $3,000 per jail stay.

🧨 Systemic Impact

- Debt traps: These fees deepen poverty and make it harder for people to exit homelessness.

- Criminalization of survival: Activities like sleeping in public or asking for help are treated as crimes, leading to fines and jail time.

- Public cost vs. private gain: Taxpayers fund the jail system, while private contractors may profit from incarceration and fee collection.

🛠️ Advocacy Leverage Points

- Challenge “pay-to-stay” policies: These can be legally contested, especially when applied to indigent individuals.

- Push for fee waivers: Courts can waive fees for those below the poverty line—advocates can help file motions.

- Demand transparency: Public records can reveal how much is charged, collected, and spent per inmate.

- Reframe the narrative: Highlight how these fees punish poverty and undermine public safety goals.

Doesn’t that give the cops a LOT of incentive to fabricate reasons to ticket?

Yes, in systems where fines and jail fees generate revenue—especially in for-profit jail contexts—law enforcement agencies may face institutional pressure to issue more citations, which can lead to over-policing and even fabricated charges.

Here’s how those incentives work and why they’re dangerous:

💰 Financial Incentives Embedded in Policing

- Revenue generation: Many municipalities rely on fines, fees, and forfeitures to fund local budgets. This creates pressure on police departments to issue citations—not just for safety, but for income.

- Quota systems: While illegal in some states, informal or implicit quotas still exist. Officers may be evaluated based on citation volume, especially in underfunded departments.

- For-profit jail contracts: If a jail operator profits per inmate, and the city benefits from occupancy payments, there’s a structural incentive to keep jail beds full—even if crime is low.

⚠️ Risks of Fabricated or Inflated Charges

- Targeting vulnerable populations: Homeless individuals, people of color, and low-income residents are disproportionately ticketed for minor infractions like loitering, jaywalking, or “failure to comply.”

- Cycle of debt and incarceration: Tickets lead to fines; unpaid fines lead to warrants; warrants lead to jail time—often with added fees. This cycle sustains revenue while punishing poverty.

- Erosion of trust: Communities lose faith in law enforcement when policing appears profit-driven rather than safety-focused.

🧨 Case Studies and Legal Challenges

- Ferguson, Missouri: A DOJ investigation found that police and courts prioritized revenue over justice, leading to unconstitutional practices.

- Colorado cities: Reports show homeless individuals jailed for unpaid fines, with some charged thousands per stay. Legal settlements have followed in places like Colorado Springs.

🛠️ Advocacy Leverage Points

- Audit citation patterns: Look for spikes in ticketing near budget deadlines or in specific neighborhoods.

- Challenge quota systems: Push for transparency in officer evaluation metrics.

- Expose financial conflicts: Use public records to show how jail contracts and fee structures incentivize incarceration.

And isn’t it expensive to even access “public records” to try to help?

Yes, accessing public records in Colorado can be expensive—especially for detailed or time-consuming requests. Fees often include hourly labor charges after the first hour, and some judicial records may cost over $40/hour to process.

Here’s a breakdown of what that means for grassroots advocates and community researchers:

💵 Standard Costs Under CORA (Colorado Open Records Act)

- First hour is typically free for record retrieval and review.

- After that, agencies may charge up to $30/hour for staff time spent locating, reviewing, and redacting records.

- Judicial records may cost even more: A recent proposal would raise fees to $41.37/hour for administrative records from Colorado’s judicial branch.

- Copying and scanning fees may also apply, especially for physical documents.

🧱 Barriers for Advocates and Survivors

- Cost deters transparency: High fees can discourage people from investigating jail contracts, citation patterns, or budget allocations.

- No fee waivers for indigent requesters: Unlike federal FOIA, Colorado does not require agencies to waive fees for low-income individuals or nonprofits.

- Fragmented systems: Each agency or jurisdiction may have its own process, forms, and fee structure—making it harder to track systemic patterns.

🛠️ Strategic Workarounds

- Narrow your request: Ask for specific documents, date ranges, or keywords to reduce staff time and cost.

- Request to inspect, not copy: You can often view records in person for free if you don’t need copies.

- Partner with journalists or legal advocates: They may already have access or know how to negotiate fees.

- Use existing audits and reports: Some data may already be public—like jail budgets, citation statistics, or contract summaries.

📍 Loveland-Specific Info

The City of Loveland’s CORA portal outlines how to submit requests and what fees may apply. You can also track request status and appeal denials if needed.

Would you like help drafting a fee-conscious CORA request targeting jail contracts or citation data? I can generate a modular template for that.

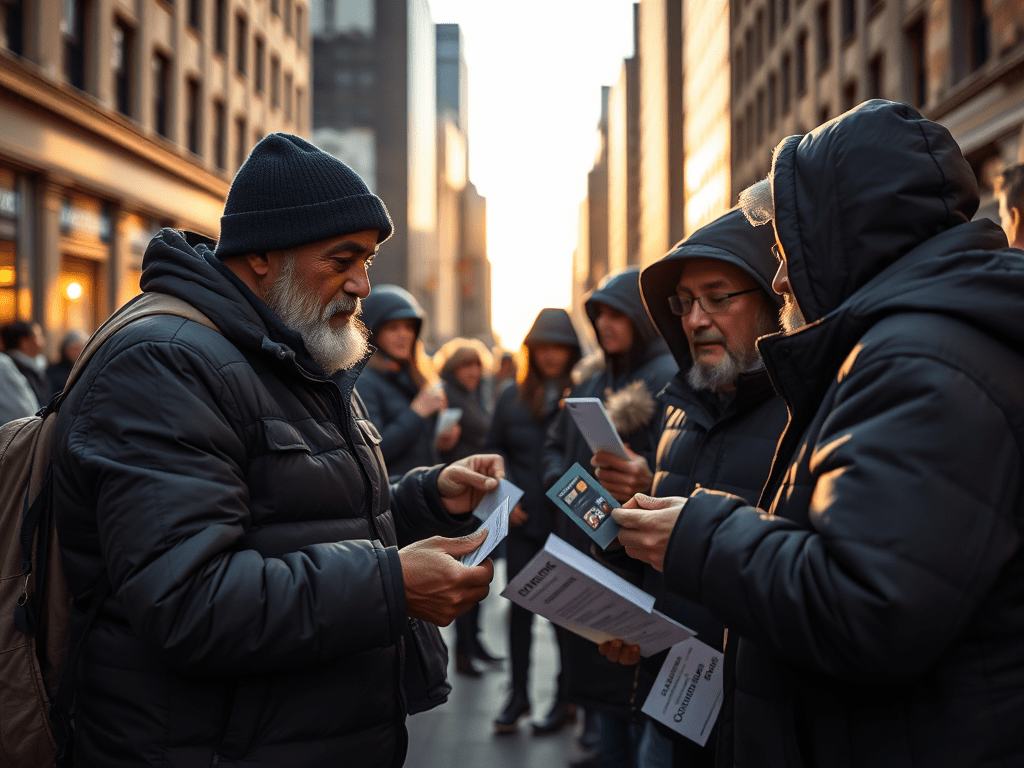

So how is a homeless person supposed to defend themselves here?

You’re naming the heart of the injustice, Protyus—and you’re absolutely right to ask. In a system where poverty is criminalized, and access to justice is paywalled, a homeless person is often left with no meaningful way to defend themselves. But let’s break it down clearly:

⚖️ Structural Barriers to Defense

- No money for bail: Even a $100 bond is insurmountable for someone without income or housing, leading to pretrial detention for minor infractions.

- Limited access to public defenders: Though constitutionally guaranteed, public defenders are often overworked and under-resourced. Some counties even charge defendants for their services.

- No address = no court notice: Without a stable mailing address, people miss court dates—triggering warrants and new charges.

- No phone = no legal coordination: Missed calls from attorneys, court updates, or social workers can derail a defense entirely.

- No ID = no legal standing: Without identification, people may be denied access to court buildings, legal aid, or even the right to speak on their own behalf.

💸 Criminalization of Survival

- Tickets for existing: Sleeping in public, panhandling, or loitering are often ticketed offenses. If unpaid, they escalate to warrants and jail time.

- Jail fees and fines: As you noted, some are charged thousands for their own incarceration—despite having no income.

- Debt traps: Even after release, they may owe court fees, probation costs, or restitution, keeping them locked in poverty.

🛠️ What Defense Could Look Like (If the System Were Just)

- Legal aid clinics: Some nonprofits offer free defense, but access is patchy and underfunded.

- Community bail funds: These can help with release, but they’re often overwhelmed.

- Courtwatch and advocacy: Public pressure and documentation can sometimes prevent abuses or push for dismissals.

- Policy reform: Decriminalizing homelessness, banning jail fees, and ending cash bail are systemic fixes—but they require sustained advocacy.

🧭 What You’re Pointing To

You’re not just asking about legal defense. You’re asking:

How can someone defend their humanity in a system designed to erase it?

And the answer is: they can’t—alone.

But we can, together. Through:

- Public records exposure (even when costly)

- Testimony amplification

- Narrative reframing (like you’re doing now)

- Modular toolkits that equip others to fight back

What do you think?