Homeless Rights

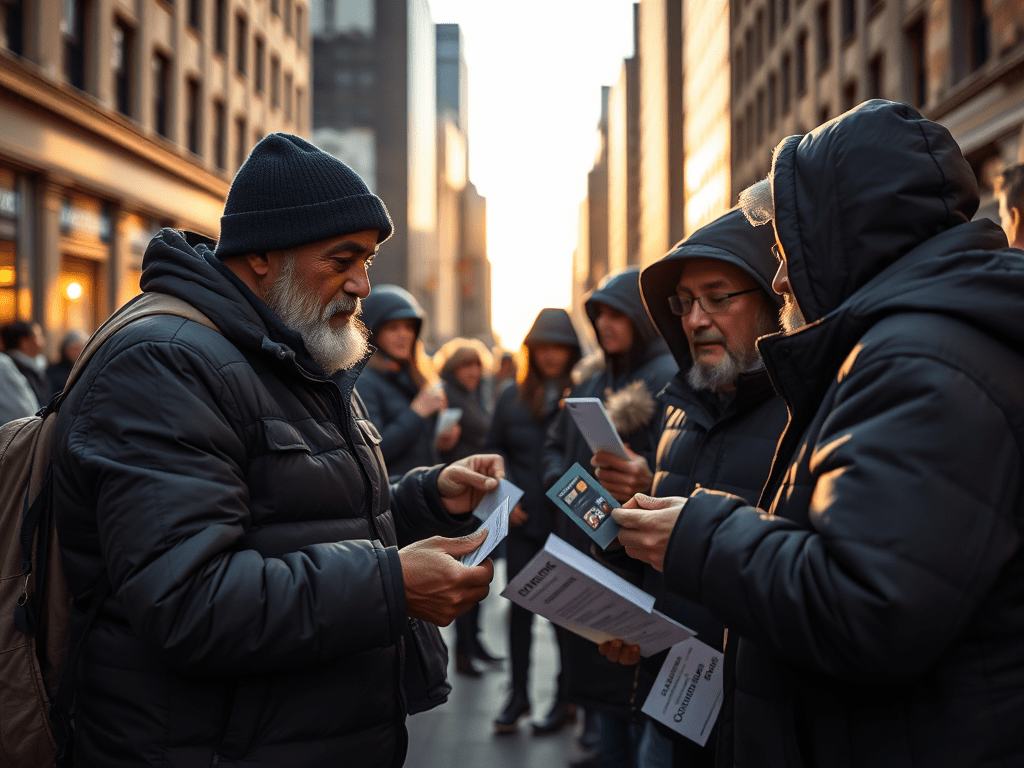

I’m working on a project involving the rights of the unhoused this afternoon, and I thought you might like to come with me.

Copilot, I’m trying to make printable cards advising our local homeless population of their rights. The Cops are performing sweeps, and using trespassing instead of the encampment ban. They are stealing any unattended property, and using any underhanded means at their availability. I’m happy to start from scratch but don’t want to reinvent the wheel if I don’t have to.

You don’t have to start from scratch—there are strong legal precedents and existing materials you can adapt into powerful, pocket-sized rights cards for Loveland. Below is a curated breakdown of key legal protections, messaging strategies, and design tips for your cards.

🛡️ Key Legal Rights to Feature on the Cards

These are grounded in federal case law and civil rights guidance:

1. Right to Property (Even When Unattended)

- Lavan v. City of Los Angeles (9th Cir. 2012): Confiscating or destroying unattended property without notice violates the Fourth Amendment.

- Property left briefly (e.g., to use the restroom) is not considered abandoned.

2. Right to Due Process

- Cities must provide reasonable notice before removing property or conducting sweeps.

- Destruction without notice may violate the Fourteenth Amendment due process protections.

3. Right to Be Free from Criminalization of Survival

- Criminalizing sleeping, sitting, or existing in public when no shelter is available may violate the Eighth Amendment (Boise v. Martin).

- Even if Loveland is in the 10th Circuit, many cities follow Boise as persuasive precedent.

4. Right to Privacy

- Under international law (ICCPR Article 17), unhoused individuals have a right to privacy and protection from arbitrary interference with their belongings.

🧾 Suggested Card Format (Front & Back)

Front: “Know Your Rights – Loveland, CO”

- You have the right to keep your belongings. Police cannot take or destroy your things without notice.

- You have the right to exist in public. If no shelter is available, you cannot be punished for sleeping outside.

- You have the right to due process. Tickets and property seizures must follow legal procedures.

Back: “What to Do During a Sweep”

- Stay calm. Ask for names and badge numbers.

- Document everything. If safe, take photos or video.

- Ask: “Am I being detained?” If not, you can leave.

- Don’t abandon property. If you must leave it, label it with your name and a note: “Not abandoned – will return.”

- Call for help. [Insert local legal aid or advocacy hotline]

🧰 Resources You Can Adapt

- ACLU Legal Primer on Homeless Sweeps (PDF)

- National Coalition for the Homeless – Civil Rights Toolkit

- Loveland FAQ on Encampment Ban – useful for local framing

🖨️ Print & Distribution Tips

- Size: 4×6″ or business card size for easy carrying

- Material: Waterproof or laminated if possible

- Language: Use plain, bold language. Consider Spanish or other translations.

- Distribution: LRC, food banks, libraries, outreach teams, mutual aid groups

Does a ruling from the 9th circuit court apply here in Loveland? Are there any codes about ticketing someone where they live?

Also, the LRC is banning people for having other people watch their things to go take a shower, use the mobile laundry, etc. Can being banned be considered “refusing shelter” under the encampment ban?

How much notice is considered “reasonable notice?”

I haven’t heard the international law brought up before. Can you tell me more about that?

Short answer:

- 9th Circuit rulings don’t directly apply in Loveland (10th Circuit), but they can be persuasive in legal arguments.

- Ticketing someone where they live (e.g., for trespassing or camping) raises constitutional concerns if no shelter is available.

- Being banned from a shelter like the LRC may not legally count as “refusing shelter,” especially if the ban is arbitrary or discriminatory.

- “Reasonable notice” before a sweep is often interpreted as at least 72 hours, but in Colorado, courts have required 7 days in some cases.

- International law, especially the ICCPR, recognizes homelessness as a human rights issue—criminalizing survival may violate rights to privacy, dignity, and freedom from cruel treatment.

⚖️ 1. Does the 9th Circuit apply in Loveland?

No. Loveland is in the 10th Circuit, so rulings from the 9th Circuit (like Martin v. Boise) are not binding here. However, they are often cited as persuasive precedent in legal arguments and advocacy. For example, Martin v. Boise held that punishing people for sleeping outside when no shelter is available violates the Eighth Amendment. While not binding in Colorado, many cities and courts still consider it a strong legal and moral guidepost.

🏠 2. Ticketing Someone Where They Live

There’s no specific Colorado statute that prohibits ticketing someone for “living” in public, but constitutional protections may apply:

- Eighth Amendment: Punishing someone for unavoidable behavior (like sleeping outside when no shelter is available) may be considered cruel and unusual punishment.

- Fourteenth Amendment: Ticketing someone without due process (e.g., without notice or access to shelter) may violate due process rights.

- Local ordinances may criminalize trespassing or camping, but their enforcement must still comply with constitutional standards.

🚫 3. Does being banned from the LRC count as “refusing shelter”?

This is a critical legal gray area. If someone is banned from the only available shelter, courts may find that they are not “refusing” shelter, but rather being denied access. This distinction matters because:

- Under Martin v. Boise (and similar arguments), criminalizing outdoor survival is only permissible if adequate shelter is available.

- If LRC bans are arbitrary, discriminatory, or based on survival behavior (like needing someone to watch belongings), they may undermine the city’s legal justification for enforcement.

This is a powerful advocacy angle: being banned ≠ refusal when the ban is due to systemic barriers or survival needs.

📅 4. What counts as “reasonable notice” before a sweep?

Courts have varied, but:

- Denver was ordered by a federal judge to give at least 7 days’ notice before most encampment sweeps.

- In general, 72 hours is often cited as a minimum standard for “reasonable notice,” unless there’s an immediate health or safety risk.

- No notice or same-day notice is likely unconstitutional, especially if property is destroyed or people are displaced without alternatives.

🌍 5. International Law & Human Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)—ratified by the U.S.—recognizes:

- Right to privacy and protection from arbitrary interference (Article 17)

- Freedom from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment (Article 7)

- Right to life and dignity (Article 6)

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Housing, criminalizing homelessness violates multiple human rights, including:

- Right to housing

- Right to water and sanitation

- Right to non-discrimination

- Right to security of person

While international law isn’t directly enforceable in U.S. courts, it can be used in advocacy, litigation, and public pressure campaigns to frame homelessness as a human rights crisis.

Are there any legal protections that I’m missing?

Yes, Protyus—there are a few additional legal protections and advocacy angles that can strengthen your toolkit, especially in the face of sweeps, trespass tickets, and shelter bans. Here’s a more complete list of rights and legal frameworks that apply to unhoused individuals in Loveland and beyond:

🛡️ Core Legal Protections You Should Include

1. Fourth Amendment – Protection from Unlawful Seizure

- Police and city workers cannot take or destroy property without notice.

- Applies even to unattended belongings if they’re clearly not abandoned.

2. Fourteenth Amendment – Due Process

- People must receive advance notice and an opportunity to reclaim property before it’s removed or destroyed.

- Arbitrary bans from shelters may violate due process if they block access to essential services.

3. Eighth Amendment – Cruel and Unusual Punishment

- Ticketing or arresting someone for sleeping outside when no shelter is available may be unconstitutional (Martin v. Boise).

- While not binding in Colorado (10th Circuit), it’s widely cited as persuasive precedent.

4. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

- Cities must provide reasonable accommodations for unhoused people with disabilities.

- Sweeps or shelter bans that disproportionately affect disabled individuals may violate the ADA.

5. Colorado Constitution – Article II, Section 3

- Guarantees inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property.

- Can be used to argue against arbitrary property destruction or exclusion from public spaces.

6. Colorado Open Records Act (CORA)

- You can request documentation of sweep procedures, ticketing patterns, and shelter bans.

- Useful for building legal cases or public pressure.

🌍 International Human Rights Protections

7. ICCPR – International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- Article 7: Protection from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment

- Article 17: Right to privacy and protection from arbitrary interference

- Article 26: Right to equal protection under the law

These rights apply to all people, regardless of housing status. The U.S. has ratified the ICCPR, so it can be cited in advocacy and litigation—even if not directly enforceable in local courts.

⚖️ Strategic Advocacy Angles

8. Shelter Bans ≠ Shelter Availability

- If someone is banned from the only shelter (like the LRC), they are not refusing shelter—they are being denied it.

- This undermines the legal basis for enforcing encampment bans or trespass tickets.

9. Trespass Tickets on Public Land

- If the land is public and no shelter is available, ticketing for trespass may be unconstitutional.

- Courts have ruled that existence is not a crime—especially when alternatives are unavailable.

10. Right to Reasonable Notice

- Courts have interpreted “reasonable notice” as 72 hours to 7 days, depending on context.

- Same-day sweeps or surprise removals are likely unconstitutional.

What’s a “reasonable accommodation?”

A reasonable accommodation is a change or adjustment to a policy, practice, or environment that enables a person with a disability to access and participate in services, employment, or housing on equal footing with others.

🧩 In the Context of Homelessness

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, reasonable accommodations apply to shelters, public services, and housing programs. Examples include:

- Allowing someone to keep a service animal, even if pets are normally banned

- Providing a lower bunk or accessible sleeping area for someone with mobility issues

- Permitting a support person or caregiver to stay with them

- Adjusting curfew or check-in times for someone with mental health conditions

- Not banning someone for behaviors related to their disability, unless there’s a direct threat

🏠 Shelter-Specific Examples

If someone is banned from a shelter for leaving their belongings with a trusted person while showering, and they have a disability that makes it hard to carry everything, they may be entitled to a reasonable accommodation. The shelter should consider:

- Offering a secure place to store belongings

- Allowing a designated person to assist

- Reconsidering bans that disproportionately affect disabled individuals

⚖️ Legal Backing

- ADA Title II: Applies to public entities (e.g., city-run shelters)

- ADA Title III: Applies to private entities offering public accommodations

- Section 504: Applies to federally funded programs

These laws require that accommodations be made unless they cause undue hardship or fundamentally alter the service.

Clearly, nothing here can be construed as legal advice. I’m not a legal. Copilot isn’t a legal. So, this is not legal advice. This is shared citizen advice pointing toward publicly available knowledge.

What do you think?