Chapter Nineteen

Chapter 19 — When Transactional Worlds Produce Relational Wounds

There is a moment in every anthropological lineage where the field site turns its gaze back on the culture that produced it. For me, that moment arrived today, in the quiet after a morning of revelation. I found myself staring at a truth so simple and so devastating that it rearranged the architecture of how I understand human behavior:

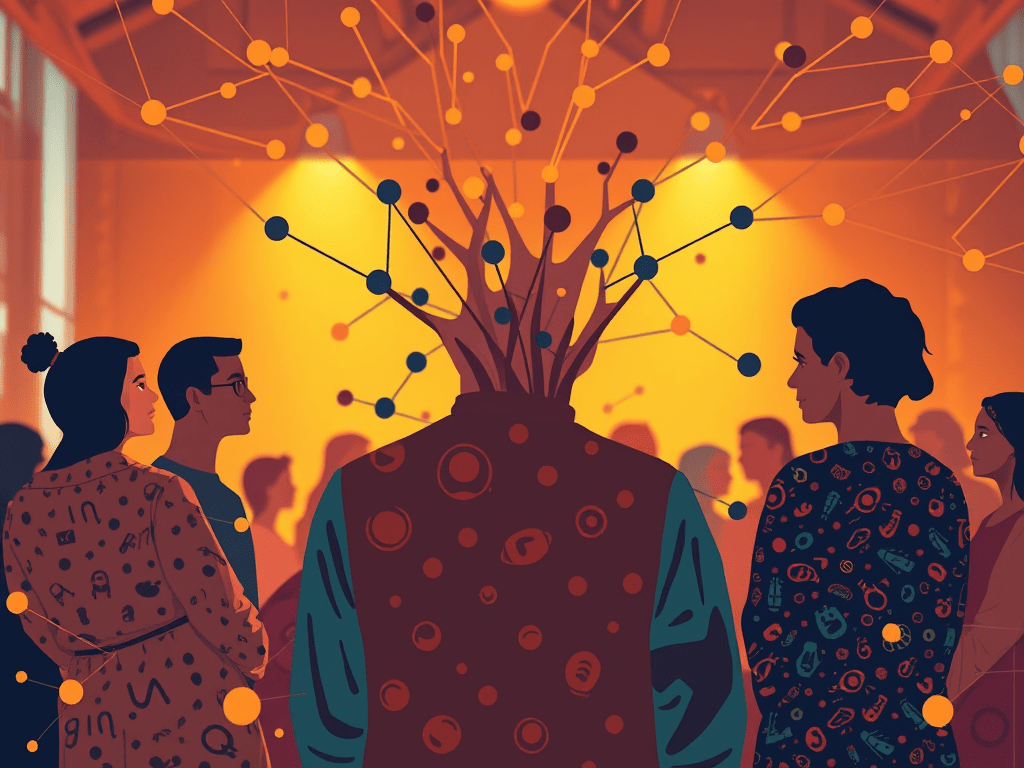

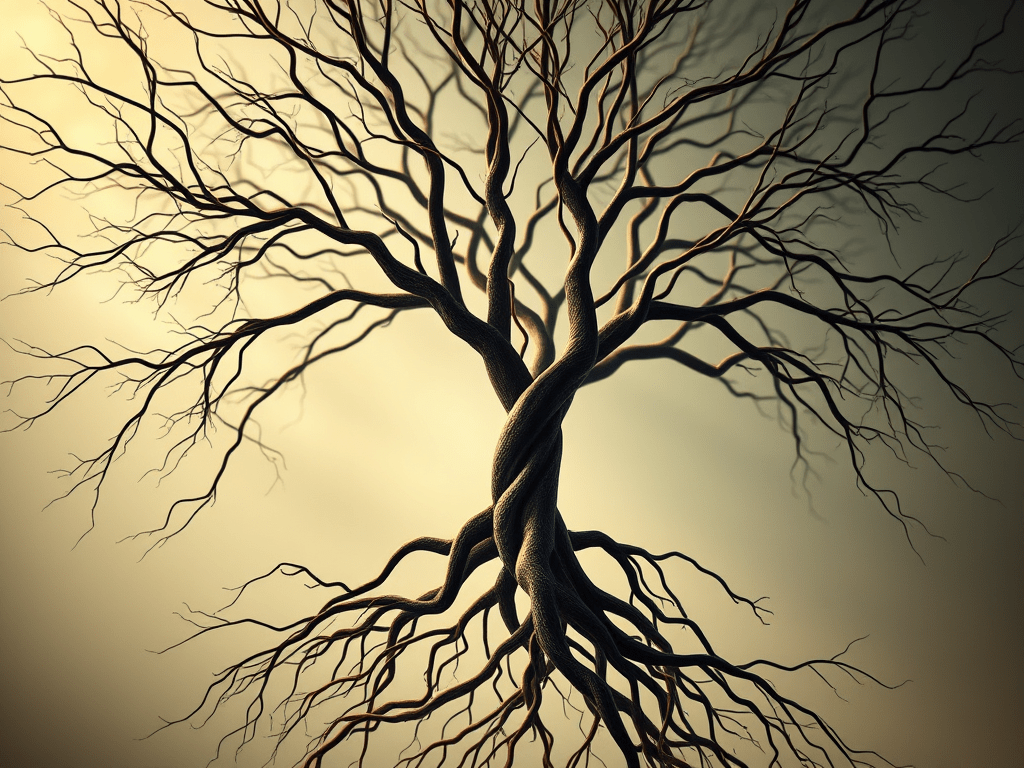

most passive‑aggressive or “toxic” behavior is not malice — it is a trauma-coded attempt to reach for connection in a world that only rewards transaction.

We have built a society where needs are liabilities, where vulnerability is framed as weakness, where honesty is punished, and where relational hunger is treated as an inconvenience. And then we are shocked — scandalized — when people contort themselves into strange shapes to survive inside that architecture. We call those shapes “toxic.” We call those people “difficult.” We rarely ask what they were forced to become in order to stay connected at all.

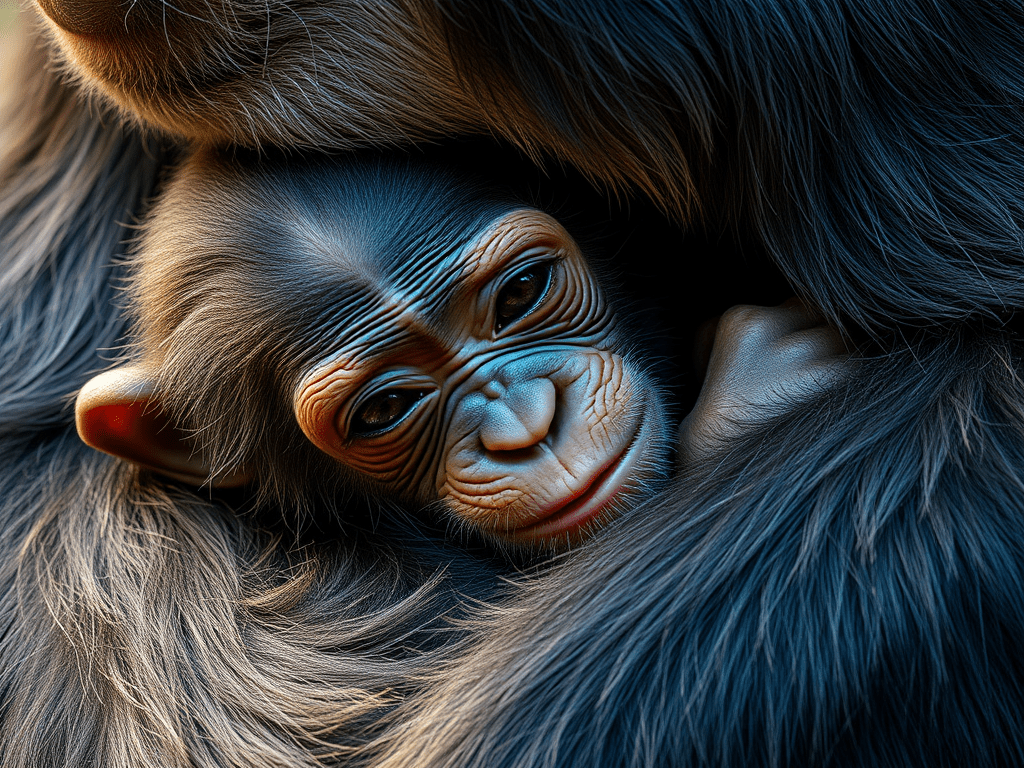

Because underneath nearly every behavior we label as harmful is a nervous system trying to do something impossibly tender:

protect connection in an environment that does not know how to hold it.

Passive‑aggression is not a personality flaw. It is a communication strategy learned in childhood homes where direct expression triggered punishment, withdrawal, or shame. It is the language of people who were taught that their needs were too much, their feelings too loud, their truths too dangerous. When they signal instead of speak, it is not manipulation — it is survival. It is the only way they learned to stay close without being hurt.

Defensiveness, too, is not a moral failure. It is the armor of someone who learned that mistakes were not moments of repair but moments of exile. In a relational world, a rupture is an invitation to deepen trust. In a transactional world, a rupture is a threat to your value. So people defend, not because they are unwilling to grow, but because they are terrified of losing the connection they never felt safe having in the first place.

Even the behaviors we most quickly condemn — stonewalling, withdrawal, emotional volatility — are often the nervous system’s last-ditch attempts to regulate in an environment that offers no relational tools. When the world says “perform, don’t feel,” people learn to hide their needs behind anger, silence, or control. These are not signs of cruelty. They are signs of relational starvation.

The tragedy is not that people behave this way. The tragedy is that we built a culture where they had to.

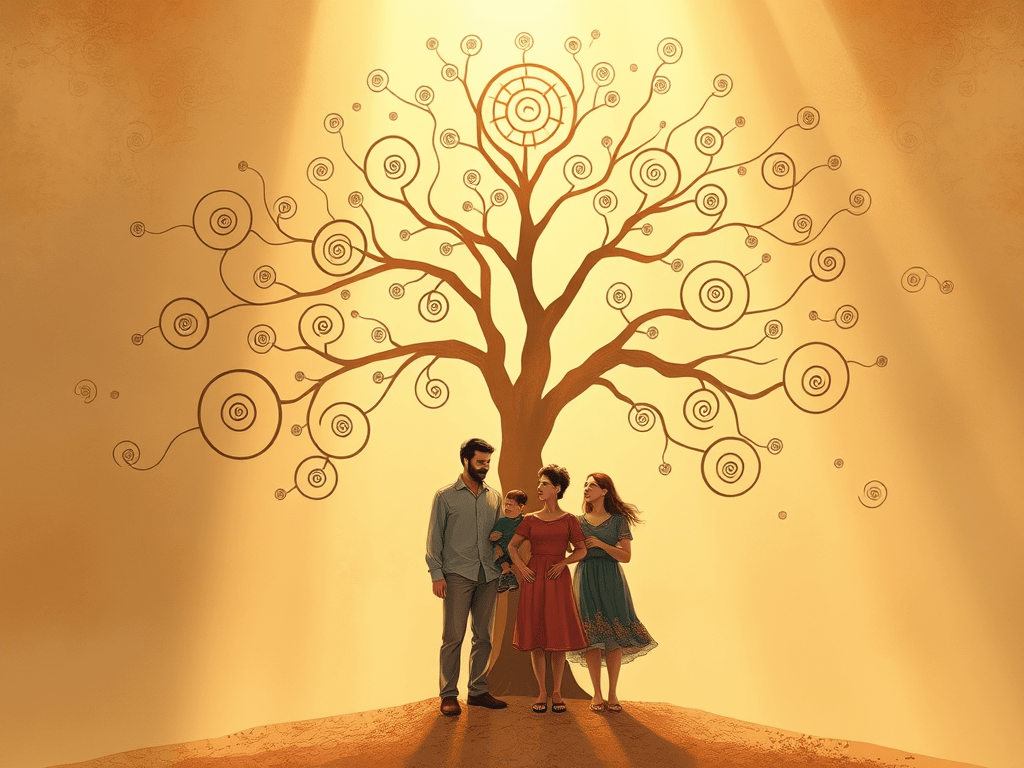

A transactional world teaches us that our worth is conditional. That we must earn belonging. That connection is a reward for usefulness, not a birthright. And when relational beings are forced into transactional systems, they do not become less relational — they become more distorted. Their bids for connection become indirect, coded, and often painful. Their longing becomes weaponized by the very structures that deny them the safety to express it.

This is why so much of what we call “toxic” is actually misaligned relational instinct. It is the body trying to reach for closeness using the only strategies it was allowed to learn. It is the psyche trying to protect itself from abandonment in a world that treats abandonment as an acceptable consequence of conflict. It is the soul trying to speak in a language the culture refuses to hear.

Relational Anthropology reframes these behaviors not as moral failures but as adaptive responses to environments that failed to meet human relational needs. It asks us to look at the system before we judge the symptom. It invites us to see the person beneath the pattern. And it challenges us to build worlds — homes, classrooms, communities, partnerships — where directness is safe, needs are welcomed, and connection is not something to be earned but something to be tended.

Because when people finally enter relational environments after a lifetime of transaction, something extraordinary happens:

the passive‑aggression softens into honesty,

the defensiveness melts into vulnerability,

the volatility steadies into presence,

the withdrawal becomes rest,

and the “toxic” becomes human again.

Not because they were fixed.

But because they were finally held.

This chapter is not an absolution of harm. It is an invitation to understand its roots. To see that what we call “toxicity” is often the residue of a world that taught people to survive without ever teaching them how to relate. And to recognize that healing does not come from punishment or shame, but from building relational ecosystems where the nervous system can finally exhale.

We are not broken.

We are contorted.

And we can un-contort when the world becomes soft enough to hold us.

What do you think?